Before becoming “The Watchdog” for the Star-Telegram (and now the Dallas Morning News), award-winning columnist Dave Lieber wrote about people and places in Northeast Tarrant County for the S-T.

We loved those columns, especially the ones we’ve reprinted below – read them and you’ll have a deeper understanding of Southlake’s history. The columns about Southlake fire and police and Dragon football tradition were written after Dave attended programs sponsored by the Southlake Historical Society.

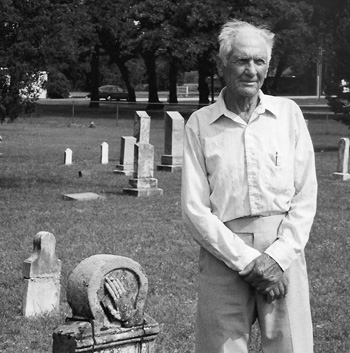

Dave’s story about Jack Cook (‘The Dove’ deserves this loyal heart) was inspired by Jack’s dedication to and reverence for the cemetery. Many of Jack’s ancestors are buried there, including Malinda Dwight Hill, who was at Parker’s Fort when Cynthia Ann Parker was taken by Comanche. Cynthia later became the mother of Quanah Parker.

Scroll down to also read and enjoy these stories:

Police and fire tales from olden days [when the mayor sold Christmas trees to raise money to buy a fire truck and all the high school boys were volunteer firemen]

One monumental Southlake story [Jones family]

Carroll has come a long way since dust bowl days [football]

Carroll’s greatest victories are lessons learned in losing [football]

‘The Dove’ deserves this loyal heart

By Dave Lieber

THE FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM

Friday, September 16, 1994

The cemetery records, being what they are, will never capture that moment of selflessness last week when Jack Cook, 76, insisted that he continue to mow the historic 2-acre Lonesome Dove Cemetery by himself – without pay. No, the official records of the Sept. 6 annual meeting of the Regular Lonesome Dove Cemetery Association will simply note that the association met and enjoyed a lovely covered-dish dinner inside the fellowship hall at Lonesome Dove Baptist Church.

The minutes will impassively state that the eight members present voted 8-0 to increase the burial fee at Tarrant County’s oldest church cemetery to $300 from $200, and that they re-elected Cook as chairman.

But the records won’t show Cook’s generosity. Nor will they capture the booted footsteps of an aging man walking back and forth across this hallowed earth – in memory of a 2-year-old son, in memory of quiet stones, in memory of all those lonesome cowboys.

For 147 years, this group and various church cemetery boards preceding it have cared for and revered this little patch of land where Tarrant County’s forebears are buried.

Lonesome Dove Cemetery, off Lonesome Dove Road in Southlake, is the final resting place for many of Tarrant County’s first pioneer settlers, first church leaders and first government officials.

Surprisingly, little has changed in a century and a half. The cost of joining the cemetery association is still $1 (or more if possible). The cost of burial remains less than at most cemeteries (and is free for those who can’t afford it).

The downside is that wind, rain, vandals and livestock have knocked over many of the gravestones, quite a few of which were only cowboy stone markers in the first place.

And it’s crowded: By some estimates, there are up to 1,600 graves within the 2.3 acres. Records were lost in a 1930 church fire, and existing records are sparse. The cemetery holds few burials these days.

But no one is discouraged.

“Well, this is my life,” Cook said. He’s a native of what he calls “the Dove” – or old Southlake. “I was born here. My grandparents, parents, wife and child are buried here – and aunts and uncles galore. Half of all the people in this cemetery were kin to me some way or another.”

In the fellowship hall that night, biscuits, fried chicken, potato salad, beef stew, watermelon, broccoli and cornbread lined a long counter.

Cook said a prayer, then invited everyone to eat.

“Thanks to Jack, the cemetery looks good,” said Coy Quesenbury, pastor at Lonesome Dove, once the only non-Catholic church between here and the Pacific Ocean. All agreed with Brother Coy.

The ensuing discussion about cemetery maintenance might seem trivial to some, but perhaps these eight people had a bigger picture in mind: Maybe through the care they give this little patch of land, they show their reverence for family, for heritage, for the idea of eternity.

How much bigger can it get?

Betty Tanner, the group’s secretary, raised the issue of Cook’s mowing. She pointed out that he has been doing it for three years. “It’s pretty difficult,” she said.

“It’s not,” he protested. “It’s pretty easy.”

No one believed him, but no one argued. Two acres and all those tombstones! And the man is 76 years old.

“It’s great,” Tanner said, “but one day we’re not going to have Jack to do this.”

There was a pause. No one said it, but everyone expected Jack to be around “the Dove” for eternity; he just might not be able to mow.

Finally, Jack spoke: “I hope to be able to do this for many more years. I enjoy it. It’s not hard. I used to mow it and Weed-eat it all in one day. Now I stretch it out over two days.”

Somebody suggested reimbursing Cook for the repairs on his equipment.

He waved off the idea, citing the cemetery’s investments: “The interest doesn’t make that much. And we never use any principal.”

He called for adjournment.

“Well, we had a pretty good crowd,” he said. It was getting dark, and Cook took a quick stroll through the cemetery. He walked fast to beat the mosquitoes.

He stopped at his wife’s grave, and the grave of their son, Tommy, who died at age 2 in a fire 44 years ago . . . and his grandparents . . . and his parents. And there – right there – was his spot. He had no use for it now, but it did need a mowing.

Cook won’t give up his mowing without a fight. And the seven others at that lovely covered-dish dinner understood why.

It wasn’t only this little patch of land at “the Dove.” It was the big picture – a reverence for family, for heritage, for the idea of eternity. How much bigger can it get?

A postscript: Jack Cook passed away Oct. 9, 2013, 11 days shy of his 96th birthday..

Police and fire tales from olden days

By Dave Lieber

THE FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM

Tuesday, July 1, 2003

Area towns were once so small that everybody knew everybody – both the good and the bad. You know you’ve lived a long time in greater Northeast Tarrant County if you can recall when every major roadway was two lanes, coyotes outnumbered people and the big question put to all the men was, “Say, how’d you like to join our volunteer fire department?”

It’s easy for residents of our fast-growing cities to forget that small-town beginnings weren’t so long ago. The other night, the Southlake Historical Society hosted a program on old-time police and firefighting. Here are a few of the stories told.

Twenty years ago, when former Fort Worth police officer Ted Phillips was appointed Southlake police chief, he thought that the officers in his small department needed to get out and greet the people.

He came up with the idea after riding with his officers in their patrol cars. He noticed that when they drove, they looked straight ahead and rarely waved hello or even looked at residents.

When he asked one officer why, the officer replied, “You know, you’ve just got to patrol, and you don’t want to get too friendly with the public.”

Not liking that answer, the new chief decided that he would have his officers walk the neighborhoods. Figuring that Halloween was as good a time as any to try this experiment, he told the officers to fan out across the community – on foot.

“You want us to walk?” an officer asked in disbelief.

“I want you to walk!” Phillips replied.

“Well, there’s kids out there,” another officer complained. “There are residents out there.”

The chief said, “Yeah, but they’re not the enemy.”

At first there was grumbling. “I was in trouble from that point forward,” Phillips told the several dozen people who attended the historical society meeting last week. “But that was one of the most positive things. We got so much energy out of that.”

Today, that style of law enforcement is called community policing, and it is used in cities around the world.

The first pumper truck purchased by Southlake’s volunteer Fire Department was a 1950 Diamond-T military unit with a 1,000-gallon tank. The pumper was used at Carswell Air Force Base to foam down the runway in case of aircraft landing problems.

Carswell agreed to sell it to Southlake for $250, former Southlake Fire Chief R.P. “Bob” Steele remembered. But first the city needed to raise the money. So the town mayor sold Christmas trees at the corner of Carroll Avenue and Texas 114, and enough money was collected.

Because there was no fire station, the pumper was parked outside Casey’s Grocery at Carroll and 114. But that caused a problem. The battery on the pumper was weak, and sometimes the engine was tough to start.

“It was really comical sometimes,” Steele said.

So somebody came up with the idea of moving the pumper to Lloyd Brown’s residence on Carroll Avenue because his land was on a hill and the truck could be backed up the hillside.

The pumper was standard shift, not automatic, so when the fire alarm rang, somebody ran to the truck, jumped in and released the clutch.

“All you had to do was roll it down the hill and get it started,” Steele said. “But you had to keep it running during the fire so you could take it back.”

The 24-volt siren was another problem. “You had to be careful how much you used it because it pulled a lot of juice,” Steele said.

Generally, he said, that crazy setup worked until the city built a fire station. But one time, “we went to a fire and everyone got there, but there was no truck. Somebody forgot to pick up the truck.”

Oops.

Not long after current acting Fire Chief Robert Finn moved to town in 1979, he noticed a burning building. The youngster ran over and asked what was happening. Firefighters told him that they were burning a house for practice.

“Son, there’s two things in this town you’re going to do,” somebody told young Finn. “One is play football, and the other is be a volunteer fireman.”

Soon after, Finn’s mother learned that the department didn’t have a Jaws of Life tool for traffic accidents, so she organized a chili cook-off to raise money.

As town legend has it, the first person to benefit from the new tool was young Finn himself, when, in 1982, he drove his brother’s car without permission and wrapped it around a tree. Firefighters removed him from the car and took him to the hospital.

Back then, the tradition in Southlake was to make hospital visits to victims of car wrecks. It was that kind of small town.

But when Bob Steele and his wife, Crystal, showed up at the hospital, the nurses wouldn’t let them in because they weren’t family.

Thinking fast, Crystal Steele shouted, “Well, I’m his grandma!”

It worked, and young Finn had visitors. He also became an official member of the Southlake “fire family.” In 1985 he began volunteering. Soon after, he went to work for the city.

Now the word around town is that Finn will become the city’s next fire chief. If so, he will follow in a great Southlake tradition of community policing and firefighting.

One monumental Southlake story

By Dave Lieber

THE FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM

Friday, July 25, 2003

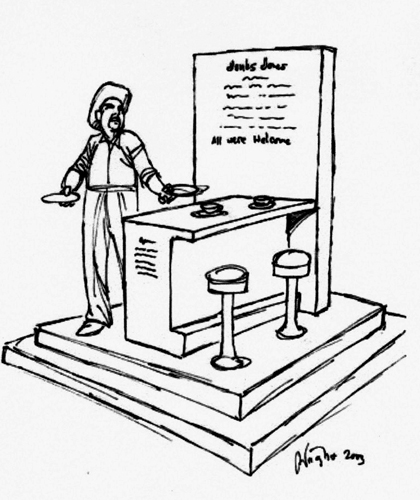

The nearly forgotten story about one of the first integrated restaurants in Texas should inspire the first public artwork in Southlake Town Square. Years ago, before the magnificent Southlake Town Square opened, its developer, Brian Stebbins, and I talked about his dream of erecting public art in the square.

Brian said he wanted artwork that represented Southlake’s history and asked for my ideas. But we struggled to come up with something that represented a growing city that previously lived in Grapevine’s shadow.

So I cracked a few jokes.

I teased that we could erect a sculpture of a soccer mom driving a minivan. Or, I asked, what about a sculpture of the perfect family living in the perfect house? Or, hey, how about someone outside Town Hall angrily waving a “Stop Apartments Now” sign?

Southlake Town Square has existed for four years, and there is still no artwork. But I have never stopped thinking about what kind of outdoor statue would bring credit to Southlake. The other day, I hit on something.

There is a little-known story about a longtime resident named Jinks Jones. He was the son of Bob Jones, for whom the new city park is named. But Jinks’ story, although nearly forgotten, is as worthy as his father’s long-standing place as one of the city’s original settlers.

Jinks and his brother, Emory, along with their wives, two sisters named Lula and Elnora, owned the Jones Cafe at Texas 114 and White Chapel Boulevard. It was next to the brothers’ livestock auction barn, which is survived today by the regular Tuesday morning flea market they once operated, too.

Both couples were black, but their restaurant was one of the few in Texas that served blacks and whites together. While the Southern world around them was deeply segregated when the cafe opened in 1949, their diner was an anomaly in Texas. Blacks and whites ate side by side with never a hint of trouble.

“The way it started, was that black truck drivers would stop on the road and they would come in the back door and ask if they could have a soda or a sandwich,” Jinks’ only daughter, Betty Jones Foreman, told me the other day in a telephone interview from her home in Houston.

“My mother told them, ‘I’ll serve you if you come in the front door.’

“They’d say, ‘I don’t want to get you in any trouble.’

“My mother would say, ‘This is a family business. I’ll serve who I want.’

“Even though we had white waitresses, Momma would come out of the kitchen and wait on them. After a few months, the white waitresses would wait on them. They never thought anything about it.”

Outside the diner, it was a different world. When the family went to the movie theater in Grapevine, they had to sit in the balcony. When they went shopping in Denton, they drank from the colored water fountains. When Betty went to high school, she rode the bus to I.M. Terrell High School in Fort Worth because she wasn’t allowed to attend Northwest High School.

But inside the restaurant, Betty told me, “The black truckers would walk in, and they couldn’t believe it. They’d sit there and look all around. They didn’t know if they were going to be snatched out and lynched. It was like they were on another planet.

“They’d sit at the counter, and here would come this old cowboy chewing tobacco, and he’d sit down on the stool next to them and say, ‘Hi, how are you doing?’ And then he’d order his red beans and chili and go on.”

There was one restroom in the back, and it wasn’t segregated, either. And in all those years, from 1949 until the Joneses got out of the restaurant business in 1973, there never was a hint of trouble, Betty said.

A big reason for the success of this improbability was Jinks himself, according to whites I interviewed.

“He was always pleasant,” former neighbor Leonard Dorsett told me. “He was very much along the lines of Will Rogers. They always said that Will Rogers never knew a stranger. Jinks always had time to acknowledge an individual in a friendly way. He reflected a Texas attitude.”

“Nobody ever thought about them being different,” Jeroll Shivers told me. “That’s the way it had always been with their dad, ol’ Bob, all the way down. They were just like everybody else. Good people. I was proud to have known them.”

“People didn’t think about whether they were black or white,” Jack Cook said. “People just mingled together. There was no talk about race at all. When you sat in the restaurant, you just sat next to whoever was there. Everyone was real friendly to everyone else.”

On Thursday, I brought this story to Stebbins at Southlake Town Square. He listened, fascinated, and said, “The thing I find intriguing is they were making history, but they were doing it in a very quiet way. And that’s refreshing.”

I told Brian that I’d like to start a campaign to bring a statue of Jinks Jones to Town Square. Ideally, it would show Jinks behind a counter talking to the white cowboy and the black trucker, sitting side by side.

I even designed a prototype for what the plaque could say:

“Jinks Jones (1895-1981) was one of Southlake’s earliest residents and one of the few African-American settlers in the area. The son of a freed slave, Bob Jones, Jinks along with his brother, Emory, and their wives, Lula and Elnora, operated the Jones Cafe from 1949-73 at the corner of White Chapel Boulevard and Texas 114.

“Almost forgotten in Texas history, the Jones Cafe was one of the first restaurants that served both whites and blacks in segregated Texas.

“For this reason, Southlake Town Square honors this almost forgotten figure in area history. The Jones Cafe represents a piece of Texas history when people put aside their prejudices and the accepted practices of the day and demonstrated as a matter of everyday routine how people could come together in a peaceful way.

“These are the goals, too, of Southlake Town Square, which strives to endow Southlake with a strong sense of community built on friendship and honor. A place that hearkens to old-time Texas, when, as Jinks Jones liked to say, ‘Your word is all you have.’ “

If my idea interests you, let me know. Let’s launch a campaign. As Brian Stebbins said, “This is something positive, which is what I like about it.”

Carroll has come a long way since dust bowl days

By Dave Lieber

THE FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM

Friday, August 27, 2004

The Dragons first played on an 80-yard football field. But after four state championships, the opener Saturday will be in the Alamodome. The Carroll Dragons, the No. 1-ranked high school football team in Texas, open the season Saturday against Midland Lee in the Texas Football Classic at the Alamodome in San Antonio.

That sentence signals success, prestige and high-voltage Texas high school football.

But it wasn’t always that way.

Sara McCombs, a Carroll district teacher and the voice of the Dragons at football games (“Now on your feet Dragon fans!”), remembers her father asking in the late 1950s, when Carroll became a school district, “How do those farmers out there ever think they could have a decent school system? How could they put together enough boys for a football team?”

The new team was called the Dragons after a Southlake softball team in the 1950s.

The first team consisted of seventh- and eighth-graders. The first “stadium” had a field only 80 yards long because there wasn’t more room.

Former Superintendent Jack Johnson remembers planting sprigs of grass on the newly leveled playing field. A water hose was connected to a faucet that tied into a deep well.

“We sprinkled that thing all day and all night,” Johnson told an audience at a recent Southlake Historical Society meeting.

“We took turns moving the sprinklers. It didn’t work.”

At the first games, the players, coaches and fans were covered in dust.

A contractor removed dirt while the first high school was under construction and extended the football field to 120 yards so there was room for end zones.

The team won its first district championship in 1965. It was also Carroll’s first graduating high school class. The team won its second district championship in 1979.

Back then, no one considered Carroll much of a football power. But that year something remarkable happened.

Bob Ledbetter arrived.

During the next 17 seasons, the coach led the Dragons to a 181-31-3 record. His teams won three state championships (1988, 1992, 1993) and enjoyed seven consecutive 10-0 seasons.

His 72-game regular-season winning streak is a state record.

I remember when the streak ended with a 43-21 loss to the Gainesville Leopards in 1994. I was on the sidelines for the final minutes. With a minute to go, the team was dragging in Dragon despair.

“Come here!” Ledbetter barked.

The team gathered around. Coach wouldn’t let them sulk.

He shouted, “You keep your heads up. You shake their hands. You show class when you’re out there. You understand me?”

The clock ran out, and the players walked to midfield. It wasn’t easy. There was a lot of pain on the faces of teen-age boys hiding behind helmets. They didn’t know how to lose. But they kept their heads up, shook hands with their opponents and showed a lot of class when they went out there.

Ledbetter taught them how to win, but he taught them how to lose, too.

Although not very often.

During the Ledbetter era, TV sports announcers praised the Dragons. “How good are these Dragons?” one 1980s-era sportscaster asked his audience. Well, they could probably beat the Cowboys, he answered.

Ledbetter coached great players like quarterback Will Mantooth, running backs David Blanchard, Mark Byarlay and Clay McNutt, and defensive ends Aaron Lineweaver and Bo Renshaw, to name a few. But his trademark was the total team concept.

“Kids can achieve extraordinary goals if they believe in themselves, and if they care about each other,” the now-retired Ledbetter told the Southlake Historical Society gathering. “It doesn’t take great athletes. Teams that win state championships aren’t teams that have great athletes. Many times, teams that have great athletes never win state championships.”

Dodge Ball came to Carroll in 2000.

Ledbetter, by then athletic director, hired Todd Dodge.

Dodge made the playoffs in his first season after losing the first three games.

In 2001, his team made it to the state semifinal game. In 2002, his team became the first in Texas history to move up from Class 4A to Class 5A and win a state championship in the same year.

Last season, his team lost the state championship by one point to Katy.

Dodge says he coined the slogan, “Protect the tradition.” He instills it in his players. Two weeks ago, at the end of two-a-day practices, Dodge called an emotional team meeting.

It was a tradition he borrowed from Ledbetter.

Every player was asked to stand in the weight room and talk about what it means to be a Carroll Dragon.

What the boys said is private among themselves.

The rest of us can only guess.

Dragon tradition began more than 40 years ago on a dusty football field that was only 80 yards long and with seating for 75 fans. On Saturday, the team will play in a domed stadium that seats about 65,000.

Says Dodge: “They started with that dirt road, and right now we’re on a superhighway.”

Note from the Southlake Historical Society: Check out a video or DVD of this program at the Southlake Public Library’s Local History section, next to the magazines.

Carroll’s greatest victories are lessons learned in losing

By Dave Lieber

THE FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM

Sunday, September 11, 1994

Vince Lombardi was wrong. Winning isn’t everything. Sometimes losing is just as good. The biggest lessons in life usually come out of defeat. Why did it happen? How can we get better? What must we do to achieve victory the next time?

Compared to all that, winning seems easy.

The last time the Carroll High School Dragons lost a regular-season football game was 1986. George Bush was vice president. The nation celebrated Martin Luther King Day for the first time. Americans dealt with two new social problems – AIDS and crack cocaine.

And Carroll lost to Springtown, 14-7.

What followed was nothing short of extraordinary. Communism fell in Eastern Europe. Bush came and went as president. And Carroll rolled through a 72-game, regular-season winning streak, a journey of perfection stretching seven full seasons.

The Streak stands as a Texas high school record.

Oh, and let’s not forget the three state football titles – 1988, 1992, 1993. Extraordinary.

At the Southlake school, winning was everything.

“They don’t know what losing a game is like,” Stephenville coach Art Briles said recently.

They do now.

At 10:35 p.m. under the Friday night lights at Dragons Stadium, the rival Gainesville Leopards ended this run of perfection with a 43-21 romp over the stunned Dragons. The Streak, and the record, stop at 72.

And on a warm summer night, there was a surprising chill in the air. The Carroll side of the grandstands grew somber and quiet, as the Dragons endured a second-half shutout that was painful for their fans to watch. The school band, usually so up-tempo, stopped playing.

Maybe the fans were so used to winning, they forgot how crowd noise – the so-called 12th man – can turn a game around. They seemed too stunned to react.

But on the far side, the Gainesville fans went berserk. The school band wouldn’t quit, and “The Electric Red Dance Team!” kept things jumping.

The Leopards’ offense was brutal, with two Gainesville players combining for 384 rushing yards and five touchdowns. And the Dragons, who this season moved up from Class 3A to 4A, kept turning the ball over to the other side.

With a minute to go, the Carroll band members found their instruments again. And the thinned-out Dragons crowd stood and cheered in a standing ovation for perfection. But on this warm summer night, there was a surprising chill in the air.

“Come here!” Coach Bob Ledbetter barked.

The Carroll team gathered around. Maybe his players didn’t know what losing was like, but Ledbetter would give them a short course. Sometimes losing is just as good.

The coach said:

“You keep your heads up.

You shake their hands.

You show class when you go out there.

You understand me?”

The clock ran out, and the players walked to midfield. It wasn’t easy. There was a lot of pain on the faces of teen-age boys hiding behind helmets. But they kept their heads up, shook hands and showed a lot of class when they went out there.

They had understood.

Compared to all that, winning seems easy.

The Carroll team limped quietly into the locker room.

Just as the crowd outside was almost mournful, the silence inside the locker room was wrenching.

The players took their seats on wooden benches. No one moved. No one said a word.

Every time an assistant coach opened a door, the players could hear the whoops of delight from Gainesville’s locker room. The only other sound was the annoying whirl of an overhead fan.

Some players closed their eyes. Others looked down at the floor. Seconds passed to minutes. Five minutes became 10. Still, no one moved.

“Get your heads up!” an assistant coach shouted. Several dozen heads lifted, and the players marched wordlessly onto the team buses for the ride back to school.

They were numb. The Stephenville coach was right. They didn’t know what losing was like.

The buses pulled out into the darkness, past a grandstand with a big permanent sign that said, “Carroll Dragons. Find a way to win.”

For eight years, they had, and it was extraordinary. Winning seemed easy. But the biggest lessons usually come out of defeat.

As coach Ledbetter said, keep your heads up and show class when you go out there. May the players carry this lesson through life. Sometimes losing is just as good.