The Missouri colonists were our first white settlers.

Meet some of the Missouri colonists and read their story below under “They brought their families, dogs, guns, religion.”

The woman who saved history

We are grateful to Pearl Foster O’Donnell, whose book “Trek to Texas 1770-1870,” published in 1966, tells stories of the Missouri colonists that can’t be found anywhere else. The first group of Missouri colonists arrived here in 1844. As we researched the Missouri colonists and the Dove community, her writing connected the dots for us many times. The pictures on this page were reprinted from her book. “Trek to Texas” can be found in the Genealogy Room of the Grapevine Library and in the Heritage Room at Tarrant County College Northeast, or read a portion at www.trektotexas.com.

One trip changed everything

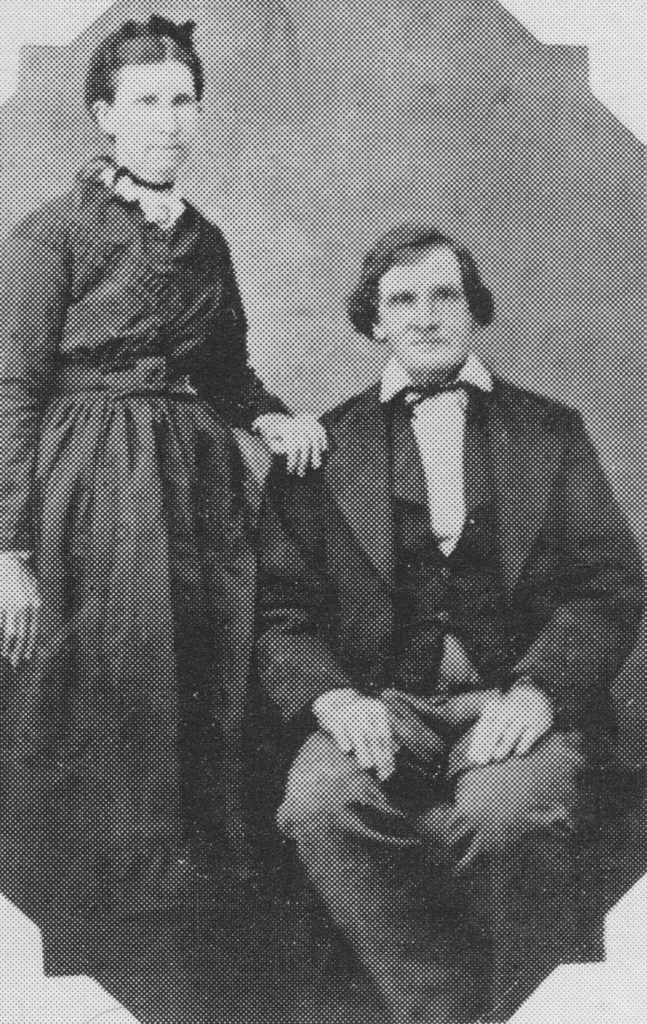

Rachel Harris and Richard Eads came to Texas with their families in the mid-1840s as members of the Missouri colony. Richard Eads’ name remains today on the official Tarrant County survey as the person who first owned the land at Highway 114 and Carroll Avenue (roads built long after the 1840s) where the 1919 Carroll School was built and still stands.

Richard and Rachel Eads left here in 1857 for California. What happened to Rachel Eads and her family on the trip will cause your heart to skip a beat. Scroll down to read “All-or-nothing trip changed everything.”

Meet a few Missouri colonists

Hall Medlin

Hall Medlin, born in 1806, was one of the Missouri settlers who made it to Texas in 1844. In 1856, he killed the last buffalo (bison) in the area but was badly gored. After crawling several miles for help, he became the first person to receive major surgery in Tarrant County.

In 1868, he came to believe that the real gold in California was beef cattle, so he led an eight-month cattle drive there that nearly turned tragic. He died in 1883 in Burnet County, Texas. He is pictured here with his third wife, Catherine.

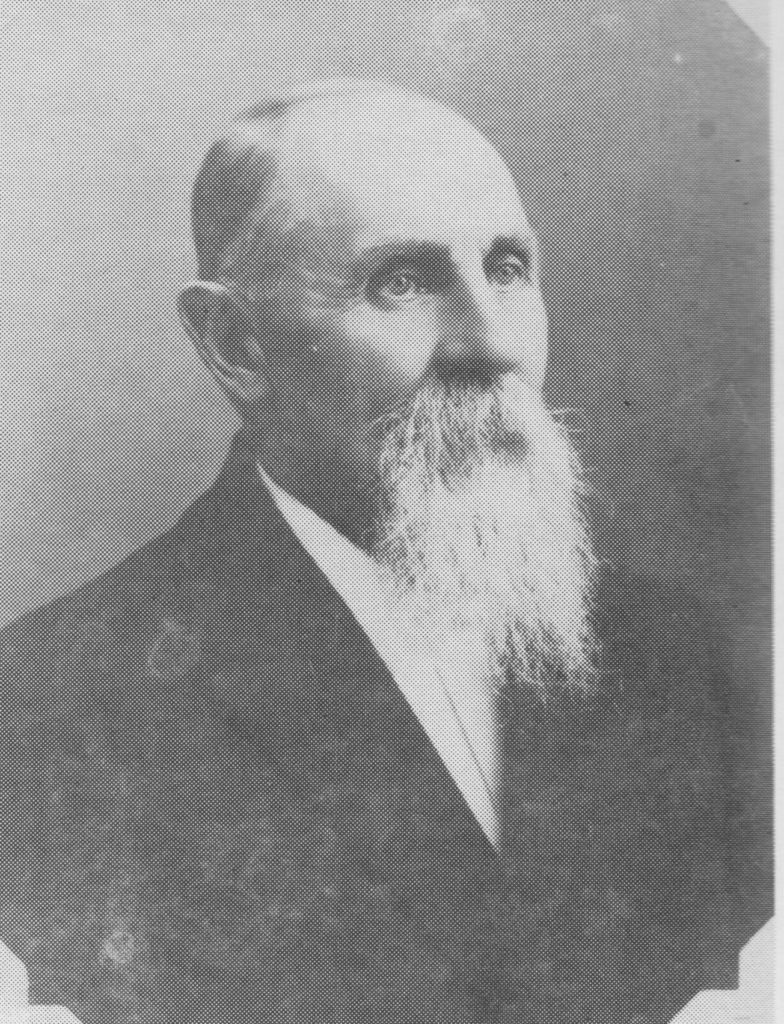

The Rev. John Allen Freeman

John Freeman was 25, newly married and filled with “the earnest desire to preach Christ in this new and strange land” when he and his wife, Nancy (Harris) Freeman, made their way to Texas in 1845.

In February 1846, John Freeman and about 10 other men stacked their guns against a tree (Indian trouble persisted into the 1870s) and, along with their wives, sisters and mothers, sat on the ground to hear the first sermon at their new church and to choose its name: Lonesome Dove.

He was ordained at the church in 1846 and was its pastor for 10 years. He also taught school there. In 1857, he and his family traveled by wagon to California, although he returned to Texas several times (by train) to attend Lonesome Dove Baptist Church homecomings. His sister-in-law was Rachel Eads — see her remarkable story about the trip west at the end of this file.

Sarah (Medlin ) Wade

Sarah Medlin, the third of Hall Medlin’s 12 children, was born in 1840. Her mother, Lucinda (Eads) Medlin, died in Missouri in 1842 after giving birth to her fourth child. Hall Medlin had not remarried by the time he left for Texas, and his four children were cared for on the journey by an enslaved woman. Sarah Medlin married Orion Wade in 1855 and moved west, losing touch with her family.

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Foster

T.J. and Sarah “Sally” (Trimble) Foster came here from East Texas in the early 1870s to join his son Joel. Members of his brother Ambrose Foster’s family were here, too.

Sally Foster, whom he married in 1858, was his third wife and the mother of the last 10 of his 24 children. T.J. Foster died in 1901 at age 92 at the home of his 24th child and is buried in Grapevine Cemetery. Sally Foster, born in 1832, died in 1909.

Jarrett Foster

When Jarrett Foster died in 1913, he was the last surviving Missouri colonist. Single and age 17 when he moved here with his parents, Ambrose and Susanah (Medlin) Foster, he received 320 acres of Peters Colony land. He married Malinda Eads. The couple and many of their 10 children are buried at Lonesome Dove Cemetery.

Ambrose Foster

Ambrose Foster, Jarrett’s father, is the only veteran of the War of 1812 (Tennessee Mounted Gunmen) known to be buried in Lonesome Dove Cemetery. In the Civil War, four of Ambrose Foster’s sons, including Jarrett, volunteered for the Grapevine Mounted Riflemen (see the Civil War section under History of Southlake).

Permelia Allen

Permelia Allen, born about 1777, was a widow in 1847 when Hall Medlin returned to Missouri to lead a group of Allens, Medlins and other related families to Texas. She received 640 acres of Peters Colony land and settled near what’s now Roanoke and Keller. Permelia Allen is one of only a few women shown on Tarrant County tax assessment lists in the 1850s, and all apparently were widows. She died in 1866.

Here is the story of the Missouri colonists

They brought their families, dogs, guns, religion

For generations, Native Americans lived and hunted in the dense forests and windswept prairies of what we know as North Texas.

In 1836 the new Republic of Texas claimed the frontier. To increase land values and create a buffer zone between the residents of central Texas and the Comanche and Kiowa, the Republic signed a contract with an investment company known as the Peters Colony. Its job was to recruit families to settle within a 16,000-square-mile area of north-central Texas and supply them with guns and food for the journey; in exchange, the investors received a portion of the settlers’ land.

(The 16,000-square-mile area later became the counties of Tarrant, Denton, Parker, Wise, Palo Pinto, most of Dallas and Grayson, and others.)

Handbills and advertisements spread the word: Bring your family to Texas, establish a farm or ranch, stay for at least three years – and get free land!

As good as that deal was, the dangers of the Texas frontier kept many people away. But not everyone.

In 1844, about two dozen related families living near present-day Kansas City (but originally from Alabama, the Carolinas and Tennessee) started for Texas. After encountering swollen streams, illness and Indians, most turned back, although a few families pushed on and settled northeast of here. The next year, two men from the group returned to Missouri to talk up the wonderful opportunities in the country of Texas.

Convinced, the families again set out for Texas. Traveling in wagons and on horseback, they shared the trail (when there was one) with backwoodsmen, land speculators, itinerant preachers, earnest settlers and misfits. They observed vast herds of buffalo, deer, antelope and wild horses. At a Texas Rangers station not far from the East Fork of the Trinity River, they saw Rangers who were “a wild, rough-looking set of men, some of them dressed in buckskin and some of them wore coon-skin caps.”

About two months after leaving Missouri, in late 1845, they reached the area of present-day Southlake, Colleyville and Grapevine. Known as the Missouri colonists, they were our first white settlers.

To their new homes, a historian wrote in 1898, they brought “their families, their dogs, guns and religion.” A descendant observed, “As a rule they were not interested in wealth or power, but were considered good providers and always ready to lend a helping hand to their friends and neighbors.”

Soon after arriving, they organized a Baptist church they named Lonesome Dove.

Married men who signed with the Peters Colony received 640 acres, and single men over age 17 got 320 acres. “Starter homes” were simple cabins, often windowless and made of logs with the bark still on. They were put up quickly to protect families from Indians, wild animals and the weather. Months or years later, when they had the time, they built log houses. Their cabins became barns or corn cribs.

In 1847, Hall Medlin led another group from Missouri to the area. Some of them founded Mount Gilead Baptist Church in now-Keller, an offshoot of Lonesome Dove. An early Mount Gilead church was burned by Indians.

The state’s contract with the Peters Colony was canceled in 1848, and new settlers began arriving. In 1857, discouraged by a drought and by how “crowded” the area had become, some Missouri colonists packed up and moved to California. Some moved west or south within Texas.

Other colonists lived out their lives here and are buried in Lonesome Dove Cemetery. A few of their descendants still live in Southlake.

Read more about our first settlers – and see pictures of some of them – on signs at the Southlake log house.

All-or-nothing trip changed everything

Rachel Harris and Richard Eads came to Texas with their families as members of the Missouri colony. They married in Texas. In 1857, they joined a wagon train that included Rachel Eads’ sister Nancy and her husband, the Rev. John A. Freeman, who had been the pastor at Lonesome Dove church. It’s not known why Richard and Rachel Eads moved west, although there had been a few years of drought in Texas. In 1857, John Freeman wrote to a friend that the area had become too crowded; they may have thought so, too.

Over the years Richard and Rachel Eads and the Freemans returned – by train – to the Lonesome Dove Baptist Church for homecomings.

Under what circumstances would you take this kind of trip? Do you think Rachel’s trip was worth the risks?

My Trip Across the Plains as I Remember It

By Rachel Eads (Born 1832)

I am now in my eighty-first year, having been in Los Angeles County for 55 years on the fourth day of December, 1912. Our trip here was both hard and dangerous. People who come here in Pullman cars with all the comforts of modern customs know nothing of the hardships. We neither came in Pullman cars nor emigrant cars nor stagecoaches, but in schooner wagons drawn by three or four yoke of oxen.

On the 15th day of May, 1857, some twenty families, 30 wagons and fifty men started from Denton, Texas, for the “Setting of the Sun” as we called it then, for then people thought that California was just the jumping-off place. Samuel Hazeltine was elected our Captain and a corporal of the guard was appointed and everything arranged in order, for the men had to take turns every night standing guard. The wagons were to travel single file, the one that drove in front one day fell behind the next day, so everyone took his turn driving in front. When the captain had decided on a camping place, the wagons were drawn around in a circle forming a corral for protection in case of attack by Indians or a stampede by cattle. The men herded the cattle outside and stood guard all night.

We got along fairly well considering there were so many women and children and so many wicked men and bronco oxen . . . until we reached Fort Davis. There we found plenty of good water and some grass. We remained there two days then started for Dead Man’s Hole expecting to get water there . . . a distance I think of about twenty miles. When we reached the place the water was dried up and it was a long distance ahead to water. We turned around and went back to Fort Davis, our company and cattle almost starved for water. We had to remain in Fort Davis for two weeks before our cattle were able to move on.

There, as was our custom, the women washed and cooked and made ready for the long hard trip across the hot desert. Our cooking did not consist of pies, cakes and salads and boiled eggs . . . but of bacon, black coffee, dried beans and bread made with water. (Such a thing as baking powder was not known in those days.) Occasionally we had a mess of dried peaches. Many anight I have washed until midnight, hung my clothes on the sage brush and the air was so drying they would be dry by morning. Then I would gather them up, put them in a sack and they were ready to wear again. Everything was discarded. . .our wagons were examined. . .not a trunk was allowed. We did our mending as we travelled.

After our two-weeks rest at Fort Davis we started from there and I think our next watering place was called Devil’s Hole. It was just a round hole in the desert and no one ever found the bottom of it. We heard that one man rode up near it on his mule and jumped off, and poor animal, starved for water plunged into it and went down saddle and all and was never seen again.

We dreaded the Pecos River so as it was usually high at that season of the year. Before we reached it the Indians slipped in one night and stole all our horses and we were driving a number of loose cattle in order to have fresh oxen in case our team gave out. The poor men were compelled to trudge through deep scorching sand on foot and drive the cattle. So when we reached the Pecos River, at the Horse Head Crossing we found it a raging torrent. The captain said we must cross for we had started with only enough provisions to last us across and if we delayed we would run out . . . with no chance to get any more. Now every wagon had a barrel lashed on the back for the purpose of carrying water from one watering place to the next. In fact, we never knew just when we would find water so we were careful never to leave a watering place without filling all the water vessels.

Well, we had to proceed, so the men took down the barrels enough to fill a wagon bed and fastened them down to the bed and lashed the running gear of the wagons, hitched four yoke of oxen to the wagon. Then they loaded as many of the company as could get on the barrels into the wagon and with two men on either side of the oxen and one on either side of the wagon to keep it from up-setting, they swam back and forth until all the women and children and all the men that could not swim and all the supplies were carried across. All the cattle swam over . . . that is, all that did not drown.

My sister and I were brave enough to cross with the first load, and we found nothing for fuel but small sage brush roots. We set to digging these roots and to making coffee for the poor men when they came over chilled. Every load that came over was given hot coffee from a tin cup (we had nothing but tin dishes).

Well, the next watering place of note, as I remember it, was the Doubtful Pass, and we had been told this was the most dangerous place on the entire route. When we were within about ten miles of the place, one of our men with a spy glass discovered a large company of men coming toward us. Judging them to be Indians, everyone was thrown into a terrible confusion. There were so many in the band we expected they would kill all the men and carry off all the women and children. Every man’s gun was put where he could get it in a moment and everything was made ready for battle. This was the only watering place for a long distance and it was small seepage . . . thus the night must be spent there in order to water all the stock. It was a small recess in the mountains, and it was surrounded by tall mountains. We had little hope of ever reaching the water, and if we did we would surely be attacked by the Indians. I got out my children’s shoes and tied them fast on their feet so that the rocks and cactus thorns would not tear their little feet in case they were carried off. By the way, we had two little girls, one four, and the other two years old.

In this dreadful state of mind we started on. We were coming toward the other company rapidly as they were mounted men, when the man with the spy glass discovered they were soldiers. They were sent from a fort on the Rio Grande to bury a lot of people who had been murdered in a train right ahead of us in the Pass. Also to look out for any other train they might see. They had sighted us and were coming to guard us through the Pass. Imagine our joyful shouts that ran through the crowd that a few moments before was so dreadfully fearful. The soldiers rode on each side of the wagons, guarding us and guiding us into the watering place. They camped all night with us. Where we stopped, there just enough room to corral our wagons. Our own wagon stood within ten feet of the spot on which a man had been killed and scalped and his hair was lying all around on the ground. And there all the wagons had been burned. The soldiers had picked up the bodies and buried them.

The next morning the soldiers led us out of the canyon and then they left us.

We made our way through all sorts of hardships, dangers, and sicknesses caused by bad water . . . for we had a great amount of alkali water. We had lain in a goodly supply of medicine and we used it when needed.

When we reached the Rio Grande River we found some Mexican settlers along the river. They knew nothing of our language and we knew comparatively nothing of theirs. I had learned a few words in their language from a brother who had been in Santa Fe during the Mexican War.

We traveled a long distance before we crossed the river at El Paso and started across to Tucson, which was a noted place. I cannot remember the distance involved here as you must remember I am writing from memory after a period of 55 years. But some distance before we reached Tucson we camped one night in a dry place . . . no water . . . no wood . . . no grass. It was about twelve miles from Fort Buchanan, in the Gadsden Purchase. Before morning we had a son born to us . . . something like Gypsy Smith . . . born on the desert under a schooner wagon. We started on as soon as we had eaten a bite and hitched up, traveling toward the Fort, twelve miles distant, where we laid up for ten days.

When we reached Tucson we found the inhabitants to be all Mexicans and Indians. They gathered around our wagons so thick we could hardly see through them. Some of them slipped three-week-old baby away and ran off with him. I missed him immediately, but he could not be found. Imagine my feelings. We were about to declare war when some of our men found the baby with some women in a little adobe hut. We were glad to get our baby back, and to get out of there as soon as possible.

As I remember it, the next trial came when we were within about twelve miles of Pima Village. It was a long dry stretch, and we had almost run out of water. We stopped, ate lunch and started on for the night. It was much cooler traveling by night and we were hoping to reach the village, which was on the Gila River, before daylight. We had not gone more than 200 yards when the oxen took fright, broke into a run with the wagons carrying the families, left the road and ran in every direction. I was sitting on the front of our wagon with my baby on my lap, the two little girls behind me. I threw my hand back and caught both the girls by their clothing with one hand and held onto my baby with the other arm. I almost smothered the baby to death. My husband was driving the oxen and they are not driven with lines like horses, and when the oxen are frightened they run like wild horses so the men have to walk beside the teams and drive them. The oxen left my husband behind and ran almost a mile before they were stopped. My limb next to the wagon bed was beaten and bruised until it was black and blue. When everything was gathered up and we were all together again, one child had been almost killed and a dead man had to be buried. There were all kinds of bruises to be doctored and it was twelve miles to water and with only a few gallons of water left in the whole train. It might occur to you that someone could have gone on and brought water back . . . but the danger of running into Indians was so great that we did not dare divide our forces.

One brave youth . . . if he is living today, deserves a Carnegie Medal: When we were on a long dry stretch trying to reach Sulphur Springs, our teams began to give out and lie down. The women and all the children who could had to get out and walk. We trudged on and finally one man had to leave his wagon; and part of the train decided to leave behind those with the tiredest teams, in order to save themselves and their own teams. Those who left us pushed on and finally reached water. Then this brave boy filled as many canteens as he could carry and braving the dangers alone, came to meet us. With his feet blistered and bleeding he found us about five miles back. We drank the water, let our teams lie down until the sun was low, then pushed through to water. There, the men got the things gathered up the best they could, built a fire of sage brush to make light, dug a hole, rolled the lad in his blankets, put him in and covered him up. By daylight things were patched up so we started on again and arrived at Pima Village on the Gila River about the middle of the afternoon, tired, thirsty, and as hungry as wolves. The Pimas were very friendly and glad to see us, but they told us they would steal a beef if we did not give them one, so we gave them a beef, and they kept their word about not stealing one. But they stole everything else they could lay their hands on! You never went into your wagon but one of them was right there. One day, while I was hunting something in my wagon they spied some red flannel I had and they wanted it . . . They were doing a little farming along the river and had raised some watermelons. They began to bring the melons to sell for the red flannel. I could get a big watermelon for a strip of flannel two inches wide and long enough to go around their heads.

From Pima we went to the Maricopa Wells, another Indian village inhabited by the Maricopas. They were friendly too but said we had given the Pimas a beef and if we did not give them one too, they would steal it. So, we had to give them one.

The Yuma Indians had come in on the Maricopas and they had a big battle right near where we were camped. The Maricopas had killed a number of the Yumas and the rest fled, leaving their dead lying on the ground near our camp. Our stay in this place was short.

From there we started across Gila Bend . . . another long stretch. We reached the Colorado River just below where the Gila empties into it. We went down the Colorado some distance, found good grass and camped for three weeks to let our teams recuperate since the long, dry sandy Colorado desert was just ahead of us. After our three week’s rest, we crossed the river. There was a small ferry there . . . a poor contrivance . . . but managed to cross with only one loss of a few cattle. Then we started for Los Angeles.

Now that we had reached the Golden State our spirits were revived. The danger of encounter with the Indians was passed and the train began to break up, everyone going his own way. A few families of us stayed together. The trip across the desert was hard, but we were elated with the thought of its being our last, long hard pull, so that it was much easier than it would have been otherwise.

At Warner’s Ranch a part of our company stopped and all of the loose cattle were left there. We started from there with two yoke of our best oxen. There was a young man and his wife who had been compelled to leave their wagon on the desert so we played Good Samaritan and took them in and cared for them. There was then, these two, my husband and myself and three children to be brought in with two yoke of tired oxen.

Our last camping place was just west of where Pomona is now located. Here, one of our oxen gave out and we had to leave the two of them and start with one yoke. There we had eaten the last bite of bread stuff and we had little of anything else in the form of food. My husband had bought a little mule from the Mexicans. He mounted the mule, left the young man to drive the oxen and started for El Monte to try to get something to eat by the time we got there . . . or to come back and meet us on the way.

There were several houses at El Monte at that time as that was a spot of damp land. The Americans who were there had settled there for the purpose of farming the land. One of these houses was a small one built California style where the Masons lived in the upper story and the lower story was the Baptist Church for preaching. Rev. Richard Fryer and Rev. Fugay were the preachers and my brother-in-law Rev. John A. Freeman who came with our train added another Baptist preacher.

Just as my husband reached El Monte he met a man who had lived in the same house with us in Texas. He had come to El Monte in 1855 and had settled there. He took my husband to his house, turned the mule into his pasture, caught two big strong horses, yoked up a big fat yoke of oxen, and then, mounting the horses and driving the oxen, they came to meet us.

I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw them . . . a man with a white shirt on! Strong horses and fat cattle! It seemed unbelievable. But the greatest shock was yet to come. “Now you are going to my house,” the man said, “and you are going to stay there until you have rested and have time to look around.”‘ Nothing else would do. When we got there the wife met us with a hearty welcome: we were invited into a real house and oh, wonder of wonders there sat a table with snowy white dishes and snowy white tablecloth. There was fresh butter, milk and vegetables. Now that was a sight to see.

Our clothes were all dingy from being washed in all kinds of water and our tablecloths had been spread right on the ground with everyone sitting around on the ground to eat.

Well, we had come to the stopping place. The next thing was to look around and see what there was for us.

I must say I have seen a wonderful change in these parts. I have seen Los Angeles grow from a small Mexican pueblo with a few hundred inhabitants, into a city of five hundred thousand. Then, there was not a house between El Monte and Los Angeles. Not one between El Monte and Cucumongo . . . and only one adobe at Cucumongo. None between El Monte and San Bernadino, which was a Mormon settlement at that time. There were a few orange trees at San Gabriel. One pepper tree in the country which stood on the east side of the Los Angeles River, near where the old bridge stands.

————————————————–

Well, I am at my journey’s end. My home has been in Los Angeles all these years. I have been back to the old home [in Texas] three times but we are always glad to get back. I would not live anywhere else. I have seen great changes in Los Angeles . . . and by faith I see greater things to come. I am a booster for Southern California. I have lived the most of my life in Los Angeles and when my time here shall end, I will be glad to leave my children and my friends in this favored spot.

Rachel Eads, 1913

Copied by Mildred Lemon Hansen from the original transcript

April 5, 1969

Lancaster, Calif.

Comments by Lonn Taylor, respected Texas historian who lives at Fort Davis: Rachel Eads was traveling on the San Antonio-El Paso Road, built by the army in 1849 and later known as the Overland Trail, as the Butterfield Overland stages used the western part of it.

I have been to Dead Man’s Hole, also known as El Muerto Spring, about 20 miles west of Fort Davis. I think what she calls Doubtful Canyon must be Apache Pass in the Quitman Mountains, just west of the present town of Sierra Blanca, although she gets her sequence mixed up as she would have crossed the Pecos before reaching Fort Davis, so she may be talking about Limpia Canyon in the Davis Mountains just north of Fort Davis. Both were well-known places for Apache attacks.

Same journey, different writer

The following is the story of the journey to California by Andrew S. Harris and relatives as told 100 years later by his granddaughter Mrs. Zorah Dell Sitton Teeter. Andrew Harris’ sister Rachel Eads wrote the preceding story.

Remembering the Sabbath Made a Difference

A group of Texas neighbors and relatives were preparing to start on a covered wagon journey to California. The year was 1857. Thirty wagons made up the “train,” all drawn by oxen. Some twenty families were represented, and about fifty additional men. There was also an extra band of cattle, horses and oxen being driven as a part of the train to fill in should any oxen become exhausted.

Many in the company were not entirely new to untried trails. My grandfather Harris, born in North Carolina, had come to Texas from Missouri in 1846 with his bride. There were then few roads for wagons, so they rode the distance on horseback, much of the time picking out their own trail. Rev. Freeman, also in the group, had made the trip in 1845 to Texas from Missouri.

It was in the month of May that the venturing company left Texas. They elected a Captain of the train and appointed a Corporal of the guard — everything was arranged carefully and strict regulations were observed.

Included in this Company were the writer’s [Mrs. Teeter’s] grandparents Mr. and Mrs. Andrew S. Harris, his two sisters, Nancy, wife of Elder John A. Freeman, and Rachel, wife of Richard Eads. Each “prairie schooner” contained a few small children. (My grandmother had two.)

Captain Hazelton of the Company was a Christian, so after the group had started traveling and were approaching the end of the first week he began wondering what the Company would want to do about Sunday. He began discussing the matter in small groups. Most of the Christians in the group were in favor of stopping for the day, making it a time of rest for the oxen, and the men and women could “strengthen themselves.” The children could exercise and play, but he met some strong opposition.

They said they “were on serious business, and had no time to be dallying with such foolishness. Besides, the food would not last, they had packed their wagons with the idea of traveling 7 days a week.” There was heated discussion on both sides. On Saturday the Captain rode up and down along the Train and announced a meeting to be held that evening around the camp fire.

All were present when Captain Hazelton called the meeting to order. He presented the matter from the Christian angle; also made a plea for the oxen that were drawing the heavy loads over newly made, rough roads. The opposition was strongly opposed and when the Captain put the question to vote, the Sunday observers carried a big majority but those opposed held their own meeting and as a result the Train was divided. At dawn they hitched their oxen to wagons and went on along — not nearly half of the wagons but a goodly company. Those who remained felt right was on their side and God’s blessing. Elder Freeman preached a sermon and they continued to hold these Sabbbath rests throughout the entire trip of seven months.

Months later, as they were crossing the bleak desert sands they spied a group of people up ahead beside the trail. Their first thought was of Indians, but soon the Captain announced they were white people with covered wagons. As they drew nearer, they discovered them to be the people from their original company. They listened to a pathetic story when they reached them. Their oxen had developed sore hooves, some so tender that their feet were bleeding. Much of their food supply was exhausted, and althought they rejoiced at the arrival of their neighbors, they were chagrined over the great mistake they had made. He who had created the oxen also had given a law: “Remember the Sabbath to keep it holy. The seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God. In it thou shalt do no work nor thou worthy cattle.” The Christian people divided their rations but had to leave [the people from their original company] until their oxen were able to travel.

“Them that honor me I will honor.” This same group of Christians had much to do with the building of the Lord’s work in Southern California.

Publication of El Monte Historical Society, Vol. 1, No. 4