SEE OUR BOB AND ALMEADY CHISUM JONES EXHIBIT ON THE HOME PAGE.

SEE JONES PHOTOS IN OUR PHOTO GALLERY, YEARS 1860 TO 1970.

BOB JONES

John Dolford “Bob” Jones (1850-1936) became a prosperous landowner in the Roanoke-Southlake area and a well-respected rancher and family man. Today he’s remembered as the namesake of Bob Jones Road, Bob Jones Park and Bob Jones Nature Center and Preserve. In 2012, Carroll ISD’s newest elementary, Walnut Grove, was named for the school he built for his grandchildren and other Black or bi-racial children who were barred from white schools.

Bob Jones was the son of a white man, Leazer Alvis Jones (1822-1879), and his slave Elizabeth (ca. 1822-1877), also known as Lizzie. Family lore says Leazer lived in the Carolinas until the 1840s, then — possibly after a youthful indiscretion — left by sea with slaves and racehorses. After spending time racing horses in Houston, he likely traveled up the Mississippi, then west on the Arkansas River to reach his new home south of Fort Smith, Ark. In the 1850 Arkansas slave schedule, a Black woman age 24 (Elizabeth) and three mulatto children (Jim, Josephine and Bob) are listed as Leazer’s property.

State and U.S. laws governed slavery. In 1859, Arkansas sought to drive free Black or mixed race people from the state. The law read:

“The Arkansas General Assembly passed a bill in February 1859 that banned the residency of free African-American or mixed-race (‘mulatto’) people anywhere within the bounds of the state of Arkansas. … On February 12, 1859, Governor Elias N. Conway, who had supported removal, signed the bill into law, which required such free black people to leave the state by January 1, 1860, or face sale into slavery for a period of one year. Proceeds from their labor would go to finance their relocation out of the state. At the time, about 700 free black people lived in Arkansas, less than in any other slave state.” — from Encyclopedia of Arkansas

In Arkansas, Leazer had a farm, not a plantation. At 100 or so acres, it was the right size for, say, raising horses, which he had experience doing. In about 1859, Leazer took Elizabeth and their children to Texas. It’s possible Leazer intended to free his bi-racial sons and daughters when they became adults, so he moved them to Texas to avoid the Arkansas law. Or he could have planned to make money from their labor or sell them. His intentions are not known, although he did seem to have a friendly relationship with them. In Texas, he bought a farm in the Medlin community, near today’s Roanoke.

In all, Leazer had five children with his slave Elizabeth and seven with his wife, Mary, who was white. Elizabeth is buried in Medlin Cemetery in present-day Trophy Club. Leazer’s Black family and white family remained friends for more than 100 years. Some of them helped us with our exhibit.

In the 1870 census, Bob, his mother and sisters are listed by name, a first for African Americans. Bob’s brother Jim and Jim’s wife and children are enumerated by name at an adjoining property. While the 1870 census indicated the Black Joneses could not read or write, it’s likely they could. They may not have wanted to stir up any anger or jealousy.

THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD TO MEXICO

A story passed down through one branch of the Jones family is that Bob assisted slaves fleeing to Mexico along a southern “underground railroad”: The runaways would take refuge in a cave about a mile from the Jones house and Bob would take them food (biscuits, jam, vegetables). It was kept a secret even from family members possibly because it was dangerous — even years later — for white people to know the Jones family had enabled property to escape. Today the cave, sometimes filled with water, is along the edge of Lake Grapevine and is on private property.

ALMEADY CHISUM

Almeady Chisum (1857-1949) was most often known as Meady, although her tombstone reads Almeady Jones. She also was born into slavery. Her mother, Jensie (circa 1837-1874), told Almeady that cattle baron John Simpson Chisum (1824-1884) was her father. When Almeady was about 1 year old, she, her mother, sister Harriet and brother were given to John as collateral for cattle being trailed west. They lived at the Chisum ranch near Bolivar (in Denton County) until about 1871, when John shifted his cattle operation to New Mexico. Jensie and her daughters then moved to Bonham, Texas.

Jensie told Almeady that John Chisum was her father, but relationships in slavery times could be complicated (perhaps based on safety rather than blood) and undocumented.

Almeady told her family she was born in Gainesville, where the Cooke County Courthouse now stands.

Jensie was a skilled cook and seamstress, as were her daughters. From the black and white sheep on the Chisum ranch, Jensie spun yarn and wove cloth to make John enough “gray tweed” for two tailor-made suits a year. Any additional cloth Jensie had time to make was hers to sell.

After her mother died in about 1874, Almeady may have earned money in Bonham as a cook or seamstress. The dresses she and her children wore in family photos taken years later were stylish and beautifully made (several Jones family handmade dresses from the 1910s have been donated to the Denton County African American Museum).

Almeady liked to tell her children and grandchildren about her life on the Chisum ranch. During the 1860s, the ranch was the Wild West — cowboys, cattle herds, Native Americans, bad guys and good guys, few conveniences, a hard life, enduring friendships.

SLAVERY IN TEXAS

Historians tell us that, generally, slavery in the West (ranches, livestock, more opportunity for owners to know their slaves) was not as harsh as slavery in the South (plantations, cotton, tobacco). But it was still slavery, a system in which it was legal for people of color to be bought and sold, raped, abused and separated from loved ones — all while being made to work without wages.

BOB IS SET FREE AND BECOMES A COWBOY

In Texas during the Civil War, Bob herded sheep for his father. After the war, Bob told his children, his father “set him free” (in 1865, two years after President Lincoln had freed the slaves) on a hill southeast of their farm (perhaps in present-day Westlake). Leazer, who during the Civil War was posted to a Texas militia that hunted deserters and dealt with Indian raiding, returned after the war to Arkansas to live with his white family (although his wife had been in Denton in 1864-’65 and had even given birth there).

Looking to earn money in hardscrabble post-war Texas, Bob signed on with trail drives heading to railheads in Kansas. Bud Daggett, whose uncle was a slave owner and called “The Father of Fort Worth,” became a good friend. Later Bud owned a commission firm in the Stockyards, which would have helped Bob buy and sell cattle.

Note: As far as we know, no proof exists that Bob joined cattle drives for John Chisum, who in the 1860s began moving his cattle operation west.

After the war, Bob and his brother Jim bought land from their father. Bob then began buying land farther east in Denton County to start a cattle and farming operation. He later told his children that he was drawn to the area because it was on Denton Creek (water for his stock) and had lots of trees (to provide shade for cattle and for firewood).

(The land, in the Eastern Cross Timbers, was not as desirable as the blackland prairie to the east and west of the timbers. Living there isolated the family from racial strife, grandson Bobby Jones said years later.)

BOB AND ALMEADY COURT, MARRY

In 1873 or ’74, it’s said Bob attended a dance in Bonham, 80 miles away, and met Almeady. (He may have already met her or known about her because of his work on cattle drives.) He invited her to the Medlin community to meet his mother. Almeady said yes, if he would come in a wagon to get her and bring his sister Georgeann. After her visit, Almeady returned to Bonham from Denton on the new Texas & Pacific Railway.

On Jan. 3, 1875, Bob and Almeady were married at Harriet’s house. (Their mother had died a year or so before; a family story tells of Jensie and Almeady being sick together in a room.) In September, Jim, the first of their 10 children, was born.

Their original house was made of logs (typical of pioneer homes). It later was covered with boards. As the family grew, more rooms were added. When finished, the house had two stories, a main room with a fireplace, four or five bedrooms, a dining room, a kitchen, and a balcony and porches all around.

Their children, born between 1875 and 1898, were Jim, Alice, Virgie, June, Eugie, Emma, Artie, Hattie, Jinks and Emory.

AN ECONOMIC ENGINE

Over the years, Bob became one of the area’s largest landowners, eventually owning 1,000-2,000 acres “free and clear” on the Tarrant-Denton county line.

Like any rancher, he dealt with bank loans, lawyers, oil and gas leases, deeds and more. The historical society has copies in its archives. Both Black and white tenant farmers grew corn and grain for his livestock. It’s said he always helped them to succeed.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CHURCH

In 1902, the family built Mt. Carmel Baptist Church near what is now Bob Jones Road and White’s Chapel. (A previous family church had been called Walnut Grove Baptist Church.) Family members remember that Mt. Carmel burned in 1964 or ’65, perhaps after being hit by lightning. Read family remembrances of the church at the end of this page.

THE VALUE OF EDUCATION

Bob and Almeady valued education and on occasion moved their children to Denton so they could attend school, but that was disruptive to their farming operation. Other times, they hired teachers, who taught at the church or in a little building outside their home.

In 1920, to benefit his grandchildren and other Black children in the area, Bob donated an acre to the county (which had created districts for white and “colored” schools and kept an accounting of the students) and had his sons and sons-in-law build the one-room Walnut Grove School. It was located near today’s Bob Jones Nature Center. Typical of country schools, it had a pot-bellied stove and one teacher for all eight grades. Grandson Bobby Jones — later a veterinarian and then the Tarrant County epidemiologist — remembers the “bonus” education he received there: as he waited his turn, he would listen to the older students recite.

By the 1940s, several families were invited to move to the Jones community so their children could attend the school. Most of the Jones grandchildren had grown up and moved away.

In 1951, Walnut Grove closed because its students (fewer than 10) were heading to junior and senior high. Because of racial segregation, Black and mixed-race children had to go to Fort Worth or another city to continue their education.

CHALLENGES OF RACE

Texas was a dangerous place for Black and mixed-race people. No doubt Bob and Almeady were taught, and taught their children, how to try to avoid trouble. Bob and Almeady had grown up around white people and had similar speech patterns and mannerisms. Also protective were Almeady’s friendships within the ranching community; Bob’s relationships with important whites in Denton and Tarrant counties; the family’s prosperity; friendships with local farmers and business people; and plain ol’ good luck.

For the most part, being of mixed race didn’t cause a problem for the family, Eugie Jones Thomas said in 1976 in an oral history. “The Jones family was raised among and with the white families. White tenant farmers worked on the Jones land. Social events and religious gatherings were shared.”

Her interviewer concluded that “Eugie recalls she felt no hostility or discrimination other than the fact that she could not go to school.”

Bobby Jones, born about 90 years after his grandfather, agreed with his Aunt Eugie when asked in 2003 whether the family suffered from discrimination. “Living out where we did, we were isolated away from a lot of the racial strife that was occurring,” he said. “My father and his family were some of the bigger landowners around, so we weren’t affected by segregation.”

JINKS JONES IN WWI

During World War I, Jinks served from July 1918 to March 1919 in the all-Black 24th Infantry, formed in 1869 as one of the Buffalo Soldier regiments.

The 24th’s missions had included

garrisoning frontier posts, battling American Indians, protecting roadways

against bandits, and guarding the border between the United States and Mexico.

In 1916 and ’17, the 24th did duty in Mexico with Gen. John J. Pershing during what was known as the Punitive Expedition. One goal was to capture Pancho Villa (which they couldn’t). The U.S. Army withdrew in February 1917.

In August 1917, the Texas Historical Commission recounts, men from the 24th mutinied at Camp Logan in Houston “after a month of abuse from white Houstonians and violence at the hands of its police department.” It became known as the Houston Riot of 1917 and resulted in the largest court martial in U.S. history. Nineteen Black soldiers were hanged.

Instead of being sent overseas to fight in WWI, the 24th was sent back to the U.S.-Mexican border.

Jinks, drafted in July 1918, received basic training at Camp Travis in San Antonio before being sent to New Mexico, where he rose to the rank of corporal. His younger brother, Emory, visited him in San Antonio for a month and participated in camp baseball games.

In fall 1918, Camp Bowie in Fort Worth became the second camp in Texas to train Black recruits. The presence of 3,000 Black men at the camp caused fear and culture shock among white citizens of the city, according to A History of Fort Worth in Black and White by Richard Selcer, Ph.D. The war ended Nov. 11, 1918, but many soldiers weren’t released from service until mid-1919.

Draft cards with the corner cut off indicated the man was Black. The draft cards of Mexican Americans and Native Americans were left whole.

BOB PASSES AWAY

Bob died on Christmas Day 1936. About 500 people, both Black and white, attended his funeral. He was buried in the “colored” section of Medlin Cemetery, in a section the Medlins had set aside for his family years before. See his obituary at the end of this page.

JONES LAND UNDER WATER

In the mid-1940s, the Army Corps of Engineers began planning Lake Grapevine. Much of the original Jones land, situated along Denton Creek, was taken by eminent domain. “Don’t sell the homeplace,” Almeady told Eugie. “The children need a place to come home to.” When the lake plan changed to include the family home and 40 acres around it, Eugie fought back. For two years. Then one day she received a letter saying she could keep the land but had to return the money. She simply slipped the uncashed checks into an envelope and sent them back.

In 1948, when Eugie was staying with her mother, the house caught on fire. Family members who rushed to help removed furniture and threw heirlooms, clothing, quilts, dishes and more out the windows. The family believes lightning may have started the fire. Today there is nothing that marks the site. Eugie and her husband subsequently built a house up the hill away from the lake.

ALMEADY PASSES AWAY

Almeady died in 1949 and is buried in Medlin Cemetery next to her husband. Her funeral was small, but many friends sent cards, telegrams and letters expressing sympathy.

JONES SALE BARN AND INTEGRATED CAFE

In 1948, Bob and Almeady’s youngest sons, Jinks and Emory, opened a livestock sale barn at Highway 114 and White’s Chapel Road after their land was taken by eminent domain for Lake Grapevine. Farmers and ranchers came for miles to attend the auctions, held several times a week.

Sisters Lula Jones (Jinks) and Elnora Jones (Emory) operated a small cafe at the auction barn. Opened in 1949, it is thought by historians to be the first integrated cafe in Texas. It was not opened as an integrated cafe, family members say. When Black truckers hauling rock to Lake Grapevine would stop at the back door to ask for a sandwich or soda, Lula would tell them, “I’ll serve you if you come [in through] the front. This is a family business. I’ll serve who I want.” Inside, everyone got along fine. Some Black truckers, however, were worried they’d be snatched out of their seats and lynched.

(For more insights into the integrated cafe, read Dave Lieber’s “One monumental Southlake story” in this website’s People section.)

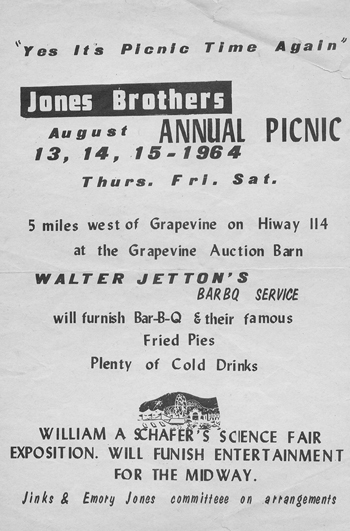

JONES COMMUNITY PICNICS

In the late 1800s, Bob Jones began hosting an end-of-harvest picnic that became a tradition. In the late 1940s, it was moved next to his sons’ auction barn. Friends and neighbors, Black and white, happily anticipated the barbecue, games and carnival rides. Some brought musical instruments and played for dances. In the picnic’s later years, it was open for three days, and it’s estimated that 1,000 people a day attended.

Wealthy Negro’s Funeral Attended By White Friends

ROANOKE, Dec. 28 – As many white people as colored gathered in the Baptist church here Sunday to pay final tribute to Bob Jones, 86-year-old negro citizen and wealthy landowner.

The crowd of 500 which jammed the white people’s church was said to be the largest funeral gathering ever witnessed in the community and the occasion itself unprecedented. Many came from out-of-town.

A negro preacher from Pilot Point had charge of the services, but the white host pastor, Rev. T. Lynn Stewart, assisted.

Elaborate floral offerings banked the casket. Burial was in a plot of the Medlin Cemetery set aside for Jones when the burial ground was established by the white owner, the late J.W. Medlin.

Bob Jones, whose full name was John Dolford Jones, founded the Jones negro settlement near Roanoke in 1870 several years after he came to Texas from a plantation near Fort Smith, Ark. He bought his first 60 acres of land from his father and at his death his property holdings amounted to about 1,000 acres, including the large two-story house in which he lived.

Denton Record-Chronicle, January 1937

Mt. Carmel Baptist Church

Mt. Carmel Baptist Church, formerly called Walnut Grove, was built some time in the late 1800s. It is not known what year the church was organized and whether it existed at another location before 1902, when it is mentioned in Baptist association records as having received a gift of $2. Services and funerals were held in the one-room church, located east of North White’s Chapel and just north of Bob Jones Road, until the 1960s. It reportedly burned in 1964 or ’65.

A grandson remembers it being about 25-by-40 feet in size.

A reference to Mt. Carmel church is found in the Dallas Morning News archives. At the 1902 meeting of the Northwestern Colored Baptist Association, “the collections amounted to $19.80. After new members had been enrolled $5 was given to educational work and $2 to Mt. Carmel Church, Denton County.” (There was also a Mt. Carmel in Dallas.)

Mt. Carmel as remembered by descendants of Bob and Almeady Jones

Betty Jones Foreman

The land [for Mt. Carmel Baptist Church] was given by J.D. (Bob) Jones. I don’t know who built the one-room frame building, probably the Jones brothers – June, Jim, Jinks and Emory – and their brothers-in-law. It was a community church almost entirely made up of Jones family. The location of the church was on White Chapel down the way from Bob Jones Road. Instead of turning on Bob Jones, just keep straight, and before you went up the little hill on the right going toward Denton Creek sat the white frame church.

I remember my mother, Lula Jones, talking about one of the [early] preachers making Bob Jones angry. He preached his sermon on what a wonderful woman Almeady Jones was, and Bob Jones was sitting right there and he didn’t mention his name. Mama said Grandpa said, “Lula, did you hear that preacher dillifing me?” That was Grandpa’s last time in Mt. Carmel church. I think that was Rev. Norton.

There was also Rev. Lister out of Fort Worth, whose wife played the piano and organized the first choir. After that it was just lay preachers out of Fort Worth or Denton. J.T. Evans (Virgie Jones’ husband) claimed he was “called,” and he filled in from time to time. Sometimes the teachers who had been hired for Walnut Grove School would stay over and play the piano on Sunday for church. Two that I remember are Aquilla Johnson out of Fort Worth and Bobbie Johnson (no relation) out of Denton. The preacher was only there on one Sunday each month, and I think that was the fourth Sunday.

Jones sisters Eugie Thomas and Virgie Evans, along with Ms. Henry, were the Sunday School teachers. Ms. Henry was Ernest Clay’s sister (Ernest Clay was married to Artie Jones). They had Sunday school each Sunday and then preaching once a month. If there was not a piano player there, we still had music. Eugie would play her one song, Virgie hers and Betty Jean hers. Same music each Sunday, but we were singing.

Occasionally there would be “Dinner on the ground,” and everyone would bring their favorite dish. We would have cabbage, fried chicken, baked chicken, stewed chicken, chicken and dumplings, macaroni and cheese, black-eyed peas, purple-hull peas, pinto beans, corn on the cob, mashed potatoes, cornbread, and etc. For dessert, sweet potato pie, peach and berry cobblers, and pound cake. Usually ice tea and lemonade to drink.

When we had a regular preacher there would be a revival. I joined church at a revival and was baptized in the stock tank on J.T. Evans’ land. Five others joined at the same time I did. I [don’t remember] the date the church burned; seems as if lighting struck it.

Venora Meeks

In the summertime, all the men would build an arbor, and every year we would have a homecoming in August. We’d have Sunday school under the arbor when it got too hot. My daddy and mama would get in the buggy and we’d go [to church] each week. We used to live in the area where Trophy Club is now. Near Medlin Cemetery – road went right by there. The preacher (once a month) would ride the train into Roanoke early in the morning and then take it back that night. My Aunt Artie played the organ.

There was a little branch [creek] behind the church, and now there are big old houses. White’s Chapel, past Bob Jones. Aunt Virgie’s husband would teach the Sunday school lesson; my daddy was a deacon, and he would pray for his mama. I was baptized in Denton Creek. After the homecoming in August, we’d take the kids who joined down to a spot in the creek and baptize the kids. My daddy would go out there with a stick and poke around to hit bottom. Probably 25 to 30 people, or even more [attended church]. Many more [came to] the homecoming.

Marie Grigsby

I have books with some Mt. Carmel minutes in them. So the last entry of anything there is dated September 1964. This particular entry is on a chart type of thing which has handwritten headings for October, November and December, but no entry after September. I guess that could mean a lot of things: The End, a new book that I don’t have, incapacitated church clerk, etc., etc. But it does coincide with the timeframe you make mention of per Bill Jones [who remembers the church building burning in 1964 or ’65].

As for funerals held there, all I can refer to are a small collection of funeral programs/memorial folders that I have from my parents’ belongings. There I find one for William “Dock” Burns (Hattie Jones’ husband) that indicates the service was at Mt. Carmel on Dec. 31, 1956, at 3 p.m. with Rev. B.F. Johnson officiating. There is also one for Rom Revels, held March 23, 1959, at 2 p.m., Rev. W.M. Bowden officiating.

Bobby Jones

I would image that Mt. Carmel was functioning for some time prior to 1902. My father was the baby of the kids and he was born in 1898. Aunt Eugie was the last of her generation living, and she died in 1985. In the late ’70s, she was attending the First Baptist in Roanoke.

The church was a one-room building, wood. painted white, with 3-4 windows on each side. It was about 25-by-40 feet in size. No steeple, no coat room, no pulpit – just a podium that the preacher stood behind, no room for the preacher, no special ornamentation like a cross or stained glass, one door in the middle of the front and about 5 benches on each side. Usually 12-15 people attended.

By the 1940s, no services or anything except on the last Sunday of the month (usually the 4th), and communion was only held when a month had 5 Sundays. There were only 12 services per year.