Location: In Bicentennial Park, off of White’s Chapel Boulevard, about a quarter mile north of White’s Chapel’s intersection with FM 1709. Look for the water tower; the log house is nearby.

Southlake’s log house is a replica that represents a house built in the 1850s by a well-off family. At 14×14 feet, it is only as big as many bedrooms in today’s Southlake. Of special interest are the supports for the back porch – they once were telegraph poles made about 1853 that ran alongside the Butterfield Stage line in Wise County.

Also interesting is that the house sits next to Bunker Hill, which settlers used as a lookout point, and Blossom Prairie, where wagon trains heading west camped. At the end of this file, read the Log House Blog detailing the building of the log house. On the History page, read about our first white settlers, the Missouri colonists, who brought “their families, dogs, guns and religion” to their new homes in Texas.

Southlake’s log house, built in 2008, is made from three log structures from the 1850s and 1860s that stood within now-Southlake: at Carroll Avenue and Southlake Boulevard; south of Southlake Boulevard on White’s Chapel; and adjacent to Summit Park in Town Square. After being stored under tarps for up to 10 years, some of the logs had deteriorated, so no one building could be reconstructed in full.

Restoration expert Bill Marquis of Denton County handmade replacement rafters, shingles, flooring, and window and door trim, then put all the parts together. No lumber-yard materials were used.

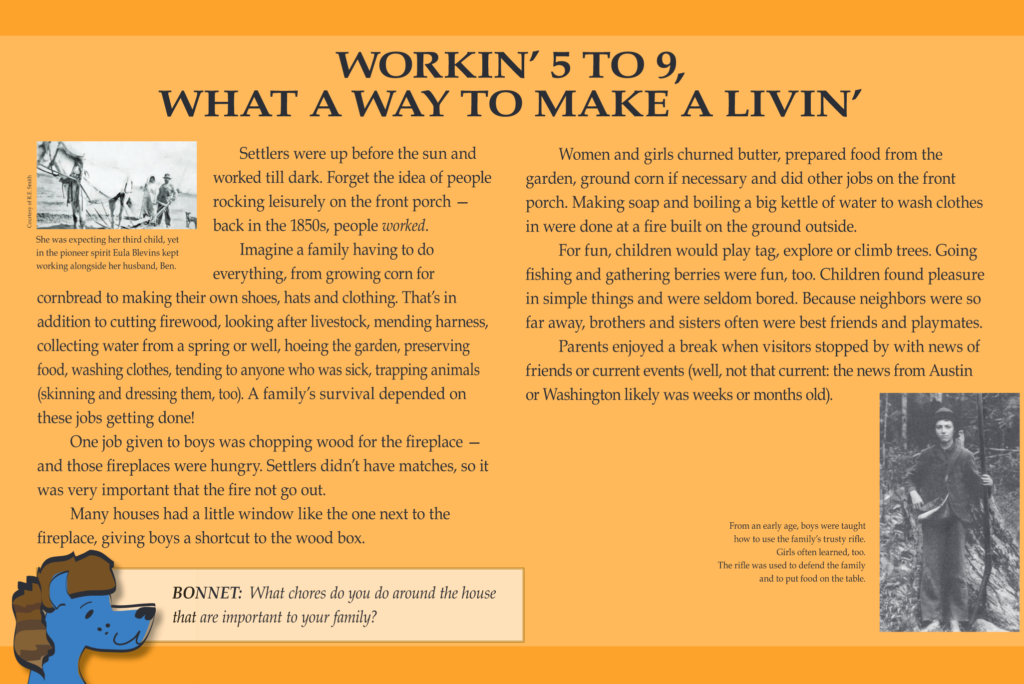

Inside, Southlake’s log house has a stone fireplace and bois d’arc mantle. Porch supports in front and back are bois d’arc, and the squared-off stones the house sits on came from the log home that stood at Carroll Avenue and Southlake Boulevard. Red sandstone for the fireplace also came from Southlake.

Wall logs are post oak, as are the rafters and shingles. The flooring is bur oak, and the shutters and doors are pecan. The red clay between the logs is local and what pioneers living here would have used.

This single-pen (one room) log house represents a popular style. Other log homes might have had a sleeping loft, a “dog trot” between two rooms, or several adjoining rooms. A log house from the 1800s would have had fewer windows, as cutting openings weakened the structure.

The city of Southlake owns the log house. Because of city regulations, it is built to code, a concept that would have left a pioneer – who judged for himself whether his house was sturdy – scratching his head.

Southlake’s log house sits on a historically significant spot. Behind it is Bunker Hill, once considered the highest point in the area (it was lowered some when the park was built). Travelers, settlers and perhaps Indians used Bunker Hill as a lookout point.

To the south, toward Tom Thumb, was Blossom Prairie, a campground that pioneers reached after a hard day’s trip from the California Crossing of the Trinity River, near what’s now Dallas. While the Eastern Cross Timbers was mostly a tangle of vines and trees, there were meadows, too, like Blossom Prairie. Plenty of wood, game and spring water made Blossom Prairie a comfortable place to camp, and it’s thought that as many as 100 wagons camped there at a time. After the travelers rested, the wagons would again line up single file and head west, for a while traveling somewhat along a route that would later become Texas 114.

Building a log house took muscle

For those who found a place to settle, building a log house took muscle. After finding straight trees as tall as 14 of 15 feet, a settler had to chop them down, hack off the bark and make the sides flat. Oxen or mules pulled the logs to the home site, which was prepared by clearing away trees, brambles and rocks. Each end of a log was “notched” so they would fit together; think Lincoln Logs. When notched, logs are placed on top of each other and the corners are fitted together, thus held together without nails.

With help from neighbors, sill logs were laid across the front and back and joined with wall logs to form a square. Then the four sides were built eight logs high. Next, doors and windows were cut, and wooden pegs were used to secure hinges and trim. Rafters made of poles were secured with pegs. Split-wood shingles and boards used at the peak ends of the roof were made by hand

Houses usually were built on top of pillars of stones to increase air circulation and prevent contact with the sometimes-moist ground and termites.

By the 1880s, times had changed. Railroads brought in “sawn lumber” and gave the average family the option of having something new and better. Sometimes people covered their log home with board siding, and years later after the original owners had died, the log house would be rediscovered

Southlake’s log house is special because

- It is constructed of logs cut down and hewn (made flat on four sides) 150 years or more ago and used to build three log structures in now-Southlake. That’s about the time Abraham Lincoln was president.

- Bill Marquis, a noted log house/cabin restorer from Denton County, built it by hand using pioneer-era techniques. He used logs from the three log structures that had been donated to the historical society. Because the logs had been improperly stored, some had deteriorated.

- The supports for the back porch are telegraph poles than ran alongside the Butterfield Stage line in Wise County.

Take a trip out to the log house to look around and discover for yourself how cool a log house is.

Signs at the log house can help you learn a lot more.

Why we call it a log house, not a cabin

When settlers arrived at a new home, they might quickly build a crude structure of stacked logs with the bark still on, called a cabin. The cabin, usually windowless, would shield the family from the weather, wild animals and Indians. Later, when the crops were in and the men had more time, a log house like Southlake’s would be built and the cabin would become a corn crib or barn.

Because our log structure is more “finished” – with hewn logs notched together, a wood floor, windows – it is a log house and not a cabin.

A good example of a cabin is the replica 1841 claims office for the Peters Colony, located in the Farmers Branch Historical Park (interestingly, Bill Marquis built it from scratch). It has walls that are round logs with bark, a dirt floor, a simpler kind of notching called saddle notching, and no windows, just several gun ports. (Notching is the way the logs are cut to fit together at the corners of the structure, like Lincoln Logs.)

In Southlake’s log house, the logs are hewn. That means each side of the log was made flat with the use of a hand adze (or, possibly, a falling or felling ax and a broad ax). The adze (or ax) is what made the “chopping” marks you see on the logs. The floor is wood; the notching is mostly half-dovetail, which is a higher quality of craftsmanship; and it has windows (although not with glass, as glass was hard to obtain) and two doors.

Sometimes men skilled in building houses could be hired to lay the sills and build up the walls – or whatever the settler was unable to do himself.

For more detail on log architecture in early Texas, visit the Texas Handbook Online.

Read on for some frequently asked questions about the log house. Further down is a blog that tells how the house was built.

FAQs ABOUT THE LOG HOUSE

Q: What year was the log house originally built?

A: Our house is a combination of three log structures that stood in what’s-now Southlake. Because the dismantled houses were stored under tarps for up to 10 years, some of the logs had deteriorated. Bill Marquis, a restoration expert who rebuilt the house, believes the structures were built in the 1850s, and the log house he has restored is representative of that time. The house he has crafted is mostly made of logs from a house that had stood on South White’s Chapel. For many years, the house had been used as a barn. That log house was donated to us by Mr. and Mrs. Lemoyne Wright.

The second log house stood until the 1990s near where Central Market is now located. It was thought to have been built in the mid-1860s, perhaps because it did not have a fireplace; by then, small, free-standing stoves were available.

The third log structure was used for years as a barn (but originally may have been a house). It stood near Southlake Boulevard adjacent to Summit Park in Town Square.

Q: Why is the log house sitting on stones?

A: Placing a house on the ground, without a foundation, had many disadvantages. Air couldn’t circulate well around the house, the logs could rot, wet weather could cause moisture to seep in, and bugs and snakes could get in. Southlake’s log house sets on red sandstone gathered in Southlake at Royal and Annie Smith Park and at a farm near Davis and Southlake Boulevard. The “hewn,” or squared off, stone you can see under the front porch came from an 1860s log house that stood until the mid-1990s near what is now DSW Shoes, in the Central Market shopping area. (It’s said it was lived in until the 1940s.)

Q: It looks like cement was used to build the fireplace. Did they have cement back then?

A: In early Texas, a variety of chimney types were made. Some were stick-and-mud, such as one you can visit at the Lake Lewisville Environmental Learning Center. Others were rock mortared with mud. Ours is red sandstone mortared with what pioneers would have called lime mortar, which is processed limestone (“lime”), sand and water, the ingredients of cement.

Craftsmen and entrepreneurs were among the settlers who began streaming into the North Texas area beginning in the early 1840s. Lime kilns to process limestone were established in both Denton and Tarrant counties. Hickory trees, once plentiful in Denton County, were cut to make charcoal, which was used to fire kilns for lime and pottery.

Q: Will the house have glass windows?

A: Glass, as you can imagine, was difficult to transport over the many bumpy miles that pioneers had to travel to reach Texas. Glass was a luxury at a time when pioneers needed so many other things. In keeping with the 1850s time period, our log house will not have glass, just shutters that open wide to let breezes in.

By the way, glass made in the 1850s was hardened with potato starch, which caused bubbles to form. It wasn’t very clear. Today, a factory in the Northeast makes this glass once a year for inclusion in historical projects.

Q: What trees were used?

A: The wall logs, cut and hewn in the 1850s, are post oak, as are the rafters and shingles, which were fashioned as part of the restoration. Bur oak is used for the flooring, and bois d’arc is used for the posts in both the front and back porches. The shutters and doors are pecan.

Q: How did the shingles get so thin?

A: Pioneers had several ways to make shingles. One involves using a froe and mallet to split shingles out of a upright log. Shingles were also cut with a pit saw that was laid over a hole in the ground. That gave the men using it the leverage they needed to make even cuts.

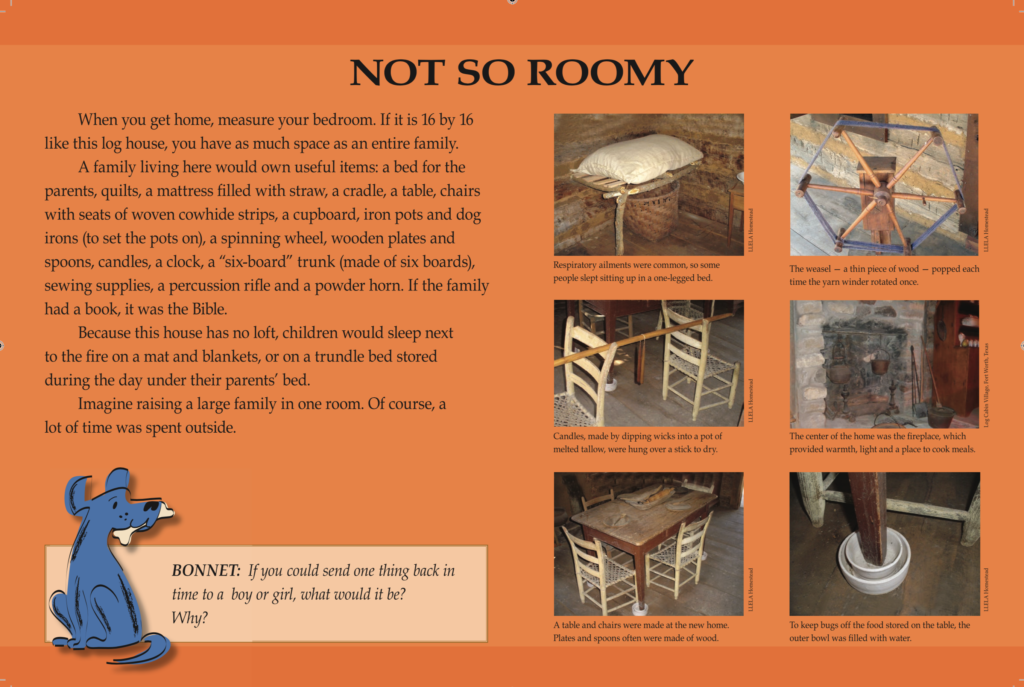

Q: Where did everyone sleep?

A: Most log houses had handmade furniture, although parents might later have a “fancy made” bed (machine-turned legs and posts). An older person might want to sleep on a one-legged Texas bed (pegged onto the wall in three places, it only needed one leg for support), which because the person slept sitting up was thought to keep respiratory illnesses at bay. Children might sleep in an attic or on pallets spread by the fire.

Q: Why didn’t termites eat all the log cabins over the years?

A: Bill tells us he’s never seen a log cabin or house that has been damaged by termites. He says that’s because pioneers knew to cut the logs during the “dark of the moon,” a few days before the new moon. Many pioneers, and even some people today, believe in doing things according to the phases of the moon in order to get the best results.

(Two other possible reasons: One, since a cabin rested on stones, the wood did not make contact with the ground and termites. Two, the wood used in the 1800s to build cabins was old-growth, virgin timber that was harder, denser and more stable than wood from younger trees. Old-growth timber also tended to have fewer knots and structural defects. That kind of wood, says people today, dried “hard as steel.”)

LOG HOUSE BLOG

December 2007

The city has hired Bill Marquis of Denton County, a highly skilled and respected restorer, to rebuild the log house. Bill has restored more than 300 log houses and cabins, including ones in Lewisville, Colleyville and Euless.

City workers have moved the logs to Bill’s farm. After choosing logs that are in the best shape, he will puzzle together a house approximately 14×14 feet. Bill is taking into account each log’s condition, length and corner notching. If important logs such as the sills are missing or in poor condition, Bill will substitute post oak logs he had cut and hewn himself.

Once Bill builds a “skeleton” of logs nine logs high, he will mark each log and disassemble the structure. The logs will be taken to the site in Bicentennial Park that’s been leveled by park workers. Bill will then rebuild the structure on a rock pillar foundation, adding doors, windows, a roof, a floor, a porch and a fireplace.

To help pay for the construction of the fireplace, the SHS is contributing the $5,000 the Southlake Women’s Club generously donated in the late 1990s for the restoration.

February 2008

SHS president Anita Robeson and first vice president Connie Cooley visited Bill Marquis at his home in Stony, Texas, to see how he was coming along with Southlake’s log house.

It was thrilling to see his progress. Using the best logs from three log structures that had stood in Southlake, Bill has fitted together a “skeleton” that will be disassembled and moved to Southlake.

Here’s what else we saw:

Logs: The corners in the rebuilt log house are primarily half-dovetail notching with few square notches (also called quarter notching). The log house that stood near where Central Market is now (at FM 1709 and Carroll) had quarter-notching; the Petarak log house (later a barn) located across Southlake Boulevard in Town Square and the log house from near Southlake Boulevard and White’s Chapel had half-dovetail notching, the most popular kind of notching, especially in North Texas. The logs are post oak, and each is about 4-1/2 inches thick. The logs Bill chose will fit together into a structure that is 16-by-16 feet (a revision in what he originally thought the size would be)

The doors and porches: The house has front and back doors. The front porch extends out eight feet, and the back porch (sometimes called a shed) is a deep overhang with steps that can be moved so pioneers could pull up a wagon for loading and unloading. Families often “washed up” on the back porch, and performed many of the endless tasks that were needed for survival, such as skinning animals, drying the skins, preparing food, etc.

The windows: There are five windows: one on each side of the two doors, and a smaller one next to the fireplace (“to pass firewood through”).

What’s next? Bill will bring the reconstructed logs to the site and begin reassembling them, then add the floor, a roof, a stone fireplace, front and back porches, door and window frames and a beautiful bois d’arc fireplace mantle. Foundation rocks that were part of the log house that stood at Carroll and FM 1709 until the 1990s (and was said to have been lived in until the 1940s) were used in the rebuilt log house.

March 2008

City workers are busy preparing the site, which is near the water tower and visible from White’s Chapel Boulevard.

By the time of our March 8 program, Bill had reconstructed the house’s “skeleton” at Bicentennial Park. Visit the park and take a look. Especially-sturdy beams called sills run along the front and back (see where Bill repaired the back sill with handmade wooden pegs). Perpendicular to the sills, along the sides, are first wall logs, lap-jointed into the sills. Stacked on top of the sills and first wall logs are hewn logs joined at the corners by notching. In all, the cabin is a traditional nine logs high. Openings were left for two doors, five windows and a fireplace. (The one next to the fireplace is to pass firewood through.)

Rock pillars are at the house’s four corners, alongside each door and the fireplace, and along the south wall (which has no windows or doors). To make these foundation pillars, Bill stacked rocks that had formed the foundation of the log house that stood near Carroll and FM 1709 from about the time of the Civil War until 1997, when the SHS disassembled it. You can see where the man who built the house used tools to square off the rocks. Rocks from Royal and Annie Smith Park and from an area near Davis Boulevard and FM 1709 will be used for the fireplace.

A floor of bur oak boards has just been laid. Underneath the boards are beams, called sleepers; they were laid about four feet apart and lap-jointed into the sill logs (the beams that run along the front and back of the house). Bill didn’t have enough old sleepers so made several replacements.

The support poles for the back porch are bois d’arc telegraph poles made about 1853. The telegraph line had run alongside the Butterfield Stage route in Wise County.

As of April 1, a few of the five windows and two doors had been framed, and Bill and his helpers had put up the “plates” (logs) that support the joists, rafters and handmade oak shingles. If he uses nails, they will be ones made during the 19th century. Or, he will use handmade wooden pegs.

After finishing the roof, porches and floor, Bill will build the fireplace, window shutters and the bois d’arc mantle. The fireplace will be an actual working fireplace, complete with a hearth of stones and a rod to hang pots on. Most pioneer cooking, however, was done by raking hot coals over the hearth and baking cornbread, etc., over the coals (and under, too, as a cook often covered a lidded pan with coals).

Log Cabin Fun

“Log Cabin Fun,” our program March 8 in Bicentennial Park, drew more than 40 people of all ages to hear restorer Bill Marquis and fiddle-and-guitar duo Tejas.

Everyone got a chance to see the log house “skeleton” up close, and Bill answered questions about the pioneer tools he brought to show, including a shaving horse, a broad axe, a pole axe, an adze, a froe, a maul and a mallet (he’s using these or similar tools on the restoration). Bill also brought an invaluable household tool called a hatchel (which had the year 1785 decorating its side, indicating it probably was a wedding gift). A hatchel looks like a block of wood with nails sticking up out of it and was used to prepare flax for spinning. In early pioneer days in this part of North Texas, clothing was mostly made of either animal skins or flax (linen).

Tejas entertained the crowd with lively and sassy, and sentimental and sweet tunes from the log cabin era. Carol Nuckols is the fiddler, and I.D. Houston plays the guitar.

April 2008

Bill has done something really special for our log house: For the back porch, he has used four bois d’arc telegraph poles made about 1853 that had run alongside the Butterfield Stage route in Wise County.

During April, Bill has framed the doors and windows, finished the porches, added oak shingles to the roofs of the porches and the living space, and chinked the house by setting rocks on top of the logs (which helps to fill in the spaces between the logs). Take a look at the nails he used to attach the door and window frames — they’re called rose-head nails and are period-correct.

If you see Bill working, he welcomes you to stop and say hello!

May 2008

As soon as the locks are added, our log house will be pretty much done! Then the city will clean up the site and add landscaping (lots of wildflowers), pathways and interpretive signs.

Over the past few weeks, restorer Bill Marquis has hand-crafted a mantle of bois d’arc supported by two “forked sticks,” and a working fireplace (the “neck” and “throat” have to be the proper size, or the fireplace will “choke,” not draw) using red sandstone found in Southlake. Straw has been chopped with an ax and mixed with red clay found near the Colleyville/Southlake border; the mixture has been daubed into the spaces between the logs. And Bill has finished the rock steps leading to the front porch.

He has finished the two doors and the shutters for the five windows. They are made of pecan wood, with hinges made of oak pegged together. Because the back windows are larger than the front, they each have two shutters that open in the middle. The front windows have one shutter. Bill has also added two “forked sticks” next to the back door for our pioneers to hang harness on.

CISD fourth-graders are in the process of visiting the house. Tours include log house history and pioneer tales. Connie Cooley, our first VP, has given teachers information about the house and the era, plus as an additional resource for teachers and students, has videotaped Bill talking about the house. Until the house is finished and inspected by the city, the children will only be allowed to walk around it.

The house will not be furnished until the SHS can raise the money to buy authentic Texas 1850s furnishings.

February 2010

We had been waiting for the city to make the log house ADA compliant, but in January council members voted not to spend the money. But that doesn’t mean the house won’t be used. The SHS is raising money to furnish it, and during tours, the windows and doors will be open so people can look in. Outdoor activities will be held for fourth-graders who are studying Texas history, and festivals will be a fun way to learn history. Extra wildflowers have been seeded around the house, so it should be extra pretty this spring. Interpretive signs are being prepared.

Summer 2010

We have been working hard on signs for the log house. The theme will be “Home Sweat Home,” since settlers had to work hard every day. Kids will want to get to know Bonnet, the blue dog who appears on the signs – Bonnet likes to play and learn at the same time.

September 2010

Signs that tell about the log house are in place, and pathways for wheelchairs are completed. The SHS is combining a grand opening with the celebration of Jack Cook Day, which by proclamation of Mayor Terrell is Oct. 16, 2010. Mr. Cook, 93, is a descendant of early settlers and the longtime caretaker of Lonesome Dove Cemetery. A ceremony was held on the back porch of the log house (a cool spot). Visitors also took a look inside the house, which is furnished with an authentic Texas log-cabin bed, a straw mattress, a coverlet, a spinning wheel, a trunk, and table and chairs. (When the house is not open, those items are put into storage.)

We hope you will visit the log house and learn from it and the signs around it. Bring a picnic lunch to eat nearby, or bring the family for a picture that you can use on holiday cards.

We hope you’ll value Southlake’s log house because

- A log cabin/house is a symbol of frontier America and the hard work, courage, self-reliance and individualism it took to move west. We still embrace these values today.

- Southlake’s rapid growth has left us with few reminders of its rich heritage. The little log house, visibly placed as an enduring symbol of our heritage, will open the door to the past for many residents and visitors to our city.

- Southlake students will see a tangible piece of history — something they can relate to when they study Texas history.

- It’s not just a log house. It’s an invitation to all ages to read about and explore westward expansion, pioneer life, U.S. history, genealogy, economics and more. Let it inspire you!